Blandine* is a beautiful, playful seven-year-old girl, who doesn't seem to notice the one thing about her that everyone else sees first: In the side of her head, in her infratemporal fossa, she has a large mass (What am I saying? Does anyone in this country have a small mass?). It extends to where her carotid artery follows its convoluted path into her brain. It impinges on five different nerves as they exit the skull on their way to her face, her tongue, the rest of her body. It, quite literally, goes for her jugular.

But to look at her, you'd never know. Her face is asymmetric, for sure, but that's about it. She's a happy seven-year-old.

So, explaining to her father that the surgery we were proposing might result in some very serious untoward events was difficult. But more than that—it destabilized the very core of the way I think about surgery. Not to put too delicate a point on it.

See, it made me question what it really meant to give informed consent.

Until Blandine, this was obvious. You go to the doctor, and she recommends a procedure. You expect that her next ten minutes are going to be spent explaining everything that could go wrong, scaring you to death with words like "cardiovascular compromise" or "cerebrovascular accidents." And then, in a perverted sort of altar call, she'll place a single sheet of paper in front of you, crammed with more words than the constitutions of some countries, and ask you to sign it. You will, probably without reading it, because that's what you're supposed to do, because in doing so you've declared that you've been informed of every possible risk, benefit, and alternative, and you still want to proceed with the surgery. Because it has become your decision.

The reasons for this are legion. There are the obvious, legal ones ones. There are the ones that place doctors firmly at fault: we want to protect ourselves, cover our rumps, in a completely self-serving way. We think that if the patient makes the decision, then we're absolved of all culpability if anything goes wrong (this is obviously erroneous).

But then there are the deeper, cultural ones, ones that I'd never thought to assume didn't exist everywhere. And it's on these that the entire concept is predicated. Very early in medical school, we learn words like autonomy and non-malfeasance and paternalism (and its more politically-correct cousin, parentalism; amazing how much stock we place on anagrams). We learn that, as doctors, we are supposed to tell you everything that could go wrong. We're supposed to give you as much information as we can. And you are the one who's supposed to make the final decision. We aren't to be paternal. You are to be autonomous. Obviously. This is so deeply ingrained in us as to be self-evident.

As it turns out, this self-evidence is, well, not self-evident. It's firmly based, instead, in the fierce individualism of our Western cultures.

After every sentence, with every enumerated risk, Blandine's father simply smiled at me and told me that she was in God's hands. No matter how strong I made my wording, no matter how bleak a picture I tried to paint, he was unwavering in this assurance. God was in control. God would bring his daughter back to him. God would make sure she was able to speak and swallow and move her face and stick out her tongue. God wouldn't let anything happen to her. This wasn't some blind, uninformed faith, either. God was really going to do this.

I found myself flummoxed. I wanted to take him by the shoulders and shake him, shake that assured smile off his face. Yes, I wanted to say, God is in control, but don't you see? Don't you understand? She might not...! He might not...! She might die! Do you hear me?

As missionaries, our objective cannot be to change the culture of a people. We do a tremendous disservice when we start believing that our way of viewing the world is the only correct way. But what happens when culture flies in the face of your own self-evidence? What if the very core on which you've built your day-to-day interactions with your patients—autonomy, self-determination—is whisked out from under you?

What if these concepts don't even enter the mind of the person you're talking to—and his overarching motifs (innate trust, for example, or determinism, or even fatalism) are themselves anathema to your Weltanschauung? Who is right? Whose worldview wins? Shall the twain ever meet?

I don't know.

I am happy to report, though, that Blandine's father's faith was borne out in the way he so inexplicably expected it to be. And in doing so, he challenged my reliance on autonomy—either as abdication or as deeply-held worldview—possibly irreparably.

And with that, I'm finishing my last post from Africa. I leave on Sunday. Thanks for following along.

Until next year.

28 March 2009

Never the twain shall meet

Posted by

M

at

3/28/2009 11:43:00 AM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Benin, Patient stories

17 March 2009

Kicking at the darkness

Two patients died earlier this week.

Now, I'll grant that in the day-to-day running of any hospital anywhere in the world, this may not seem such a significant event. People die every day. And this is doubly true in the world of head and neck surgical oncology, where the overall survival rate hovers around 50%.

Before you chastise me for being impersonal: this knowledge is just the opposite. Instead of depersonalizing, it frees the head and neck surgeon to negotiate the increasingly blurred line between physician and priest, to be fully present in someone's life at its most weighty.

But things are different on the ship. The hospital is smaller (it's a ship, after all), and most of the surgery we do is not for malignant disease. We work, instead, to restore to patients the right to look human, the right to re-enter society.

So death hits harder.

And it makes one ask: Why, then, continue? Specifically, what's the point of attempting, in our imperfect way, to heal, when all healed people eventually die? Why prolong the inevitable?

Obviously, this question isn't an original one. In the introduction to his 1849 book, The Sickness Unto Death, Søren Kierkegaard asks this of a well-known story:

And what help would it have been to Lazarus to be awakened from the dead, if the thing must end after all with his dying?

Unfortunately, his answer, though unequivocally true, is too glib to be satisfying. Perhaps a better articulation (in both the negative and the positive) comes from the Anglican Bishop of Durham, a bald, bearded man named N. Thomas Wright:

If you turn faith into simply the hope for pie in the sky when you die, and an escapist spirituality in the present, you turn your back on the theme which makes sense of the whole story... [You] may feel some sympathy for the battered and bedraggled figure in the ditch, but [your] message to him will always be that, ultimately, it doesn’t matter because the main thing is to escape this wicked world altogether.

But that's not all there is. In the Christian aesthetic, he writes elsewhere,

the world is beautiful not just because it hauntingly reminds us of its creator, but also because it is pointing forward: it is designed to be filled, flooded, drenched...as a chalice is beautiful not least because of what we know it is designed to contain, or as a violin is beautiful not least because we know the music of which it is capable.

And that is why. We do this because, in an imperfect world, we see—and have fallen in love with—the perfection for which it was intended. We do this because we know that this darkness—of sickness, of tumors, of poverty, of war—isn't what was meant to be.

We do this because we know that there is a light behind it all, and that this very world, this very creation, will one day become light—but not just one day, not just in the sweet by and by. See, here's what's most important. We work because, in working, in the smallest and most imperfect way, we might just be a bit part in that redemption, right now, right here.

So that's the crux: despite the deaths, despite the setbacks, we know that we have to kick at the darkness till it bleeds daylight.

Sometimes, though, the darkness kicks back.

Rest in peace.

Posted by

M

at

3/17/2009 06:13:00 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Benin, Patient stories

11 March 2009

Seen and sucked dry

I write this post with the unsettling knowledge that I'm firmly ensconced as part of the problem. And I have no real solution to offer.

That said, it is never pleasant to watch the insidious descent of a group of people into the indenture of tourism.

Last weekend, in an effort to see the sights of southern Benin, a group of us took an hour-long, eighteen kilometer boat ride to Ganvié. Situated in the middle of a shallow lagoon, Ganvié has been around since the 1600s (at least), a village of refuge, built on stilts. According to the story, the Dahomey warriors were forbidden, by their religion, from entering the water. And, because their prey, the Tofinu people, were intent on avoiding subjugation by the warriors, they capitalized on this fact, escaped to Lake Nokoué, and set up their town.

Ganvié has been minding its own business ever since.

However, a more nefarious sort of subjugation has begun—one which has no respect for the spirits of the lake. Supposedly (this is only hearsay; I have no corroborating evidence), Ganvié first became more widely known after it featured in a National Geographic special a couple of decades ago. Whether or not that is true, there has definitely been an inexorable incursion of tourism into the town.  Hotels are being built (one proudly sports a banner on its front awning: Buses welcome!, it says, the absence of any paved roads evidently a just minor inconvenience). The traveller is seen as a purchaser of kitsch—the obligatory stop-at-my-cousin's-art-workshop was included—and, more importantly, as the provider of useless trinkets. So much so, in fact, that children mob you the minute you enter the town, performing handstands on the bows of their ramshackle canoes, asking you for chewing gum, pens, or money, and demanding (I kid you not) that you give them the sandwich you've half eaten. So much so that the outstretched palm is one of the first gestures learned here. So much so that children are taught the important phrases early: Monsieur Madame! Yovo!* Donne moi!

Hotels are being built (one proudly sports a banner on its front awning: Buses welcome!, it says, the absence of any paved roads evidently a just minor inconvenience). The traveller is seen as a purchaser of kitsch—the obligatory stop-at-my-cousin's-art-workshop was included—and, more importantly, as the provider of useless trinkets. So much so, in fact, that children mob you the minute you enter the town, performing handstands on the bows of their ramshackle canoes, asking you for chewing gum, pens, or money, and demanding (I kid you not) that you give them the sandwich you've half eaten. So much so that the outstretched palm is one of the first gestures learned here. So much so that children are taught the important phrases early: Monsieur Madame! Yovo!* Donne moi!

It's not a far reach from here to Kyrgyzstan.

This isn't a new phenomenon. In his Studies in Classic American Literature, DH Lawrence wrote

Behold then Septimus Dodge returning to Dodge-town victorious. Not crowned with laurel, it is true, but wreathed in lists of things he has seen and sucked dry. Seen and sucked dry, you know: Venus de Milo, the Rhine or the Coliseum: swallowed like so many clams, and left the shells.

Seen and sucked dry. It's the one unifying theme in so many disparate countries. The gestures are the same, the objectification unchanged (if understandable), the power differential ubiquitous. And to this ubiquity, I find no solution. Should we not visit? Should we not see? Should we not try to understand? Should we not be travellers?

I don't think so. As Byron, himself the quintessence of wanderlust, wrote in a letter to his mother:

I am so convinced of the advantages of looking at mankind instead of reading about them, and of the bitter effects of staying at home with all the narrow prejudices of an [Englishman], that I think there should be a law amongst us to set our young men abroad for a term among the few allies our wars have left us.

If this is the case—and I think it might be—how do we avoid leaving nothing behind but shells?

Posted by

M

at

3/11/2009 05:45:00 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Benin

04 March 2009

Estragon's boot

Just on the Togolese border, about a two-hour drive west of Cotonou (it's a narrow country), sits a resort. Grand Popo, despite its particularly fetching name (which I swear I didn't make up), is beautiful.

I'm told.

Last weekend, six of us made it our destination (as much as I'd like to pretend otherwise, it's not all work here). Unfortunately, exploring West African countries isn't always a salutary experience—at least, this time, there were no car accidents.

Ready for a relaxing day in the sun, we set off out of Cotonou, and onto a dirt road that runs west along the country's shoreline. Unpaved, and relatively untrafficked, this road offers both spectacular views and a chance for you to test the mettle of both of your esophageal sphincters. And the resolve of your tires. About an hour and a half out of Cotonou, the first one blew. This wasn't going to be a problem, though. We're living in Africa, right? We know how to change a tire! And besides, any self-respecting, NGO-owned, white four-wheel-drive has a spare bolted to its roof. Ours was quite the self-respecting vehicle.

About an hour and a half out of Cotonou, the first one blew. This wasn't going to be a problem, though. We're living in Africa, right? We know how to change a tire! And besides, any self-respecting, NGO-owned, white four-wheel-drive has a spare bolted to its roof. Ours was quite the self-respecting vehicle.

What ours didn't, unfortunately, have was a jack that worked. We tried everything (pens, sticks, knives), but without a pin around which the lever could ratchet, the jack was nothing more than a bright red, human-sized metal rod.

Because a faulty jack isn't enough, our wrench was also one size too big for the lug nuts. No amount of hoping (and we did our fair share) was going to change that.

In this hopefulness, we were helped by a cadre of Beninois (their luck was no better than ours), and a few, kind, passing French families (ditto), including the French ambassador to Benin (at least, according to his wife). After an hour of jumping on wrenches, we did what anyone else would do. We called the ship for help, sat down on the side of the dirt road, and ate cheese sandwiches. The Beninois disappeared. And we got to enjoy being stranded in some of the most beautiful surroundings you could imagine.

Three hours later, the ship called back. Our erstwhile savior had gotten lost and come back home. But, another group was at a pool 12 miles away, and were on their way.

Their jack worked. Their wrench fit our lug nuts. And, with a fair amount of shouting back and forth between the us and the Beninese men that had mysteriously reappeared, we got ready to leave.

Tut tut.

"You must," I was told, "satisfy these men." Yes. Satisfy. I'm not making that up either.

We tried giving the group some money; this served only to inflame things. Volley after volley, satisfaction being more loudly demanded with every increasing incursion into personal space. Exasperatedly, I finally asked, "How am I supposed to satisfy you?" To which my interlocutor answered, "I can't tell you. It's up to you."

This was Samuel Beckett on crack. Estragon's boot wasn't ever coming off.

Instead, we piled into the car, gave them the money, and decided that their satisfaction was up to them.

We drove through Ouidah, the birthplace of voodoo (or vodoun), past the Door of No Return, commemorating the point on the coast of Abomey from which Portuguese slave ships departed with their cargo of humanity and self-righteousness, and to Casa del Papa, a mere shadow of Grand Popo. With a worse name, but, importantly, with a pool.

Everything was fine on the way back home. We stopped at an Indian restaurant for dinner, and were about 20 minutes away from the ship when, yes, the second tire blew. No working jack, no working wrench, and this time no spare, we were stuck. Another of our cars was still at the restaurant. We borrowed it, took their spare, tested their wrench, and went to jack our car up.

This time, the useless, human-sized piece of metal was bright blue. But the helpful taxi drivers that finally jacked our car up demanded no satisfaction.

Posted by

M

at

3/04/2009 01:27:00 PM

3

comments

![]()

Labels: Benin

02 March 2009

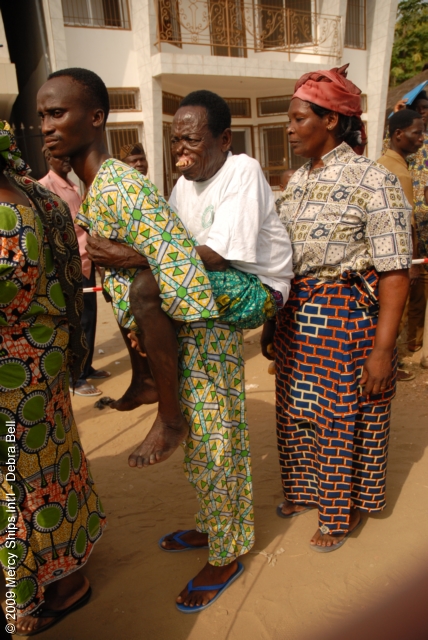

The numbers and the pictures

The official numbers—and, more importantly, the official pictures—are finally available.

2773 patients seen at our screening days

513 surgeries scheduled, and

300 patients booked for follow-up appointments prior to surgical scheduling

This doesn't include patients undergoing eye surgery—we do about 25 of these a day, nor the 30 that show up on the dock daily. Word is getting around.

Posted by

M

at

3/02/2009 04:28:00 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Benin