As if Kyrgyzstan wasn't bad enough.

Canada, according to its US embassy's website, "prides itself as an open country which welcomes immigrants and visitors." What they don't tell you (it's couched in a benign sounding injunction to "consult the links below") is that their welcome is a very conditional one. Conditional upon the whims of whichever consular agent, for example, is handling your work permit application (the things required of me this year differ significantly—and inexplicably—from those required last year).

One of the conditions placed on this love of Canada is the requirement for a medical exam. Now, I don't fault them. They're intending to hire a filthy foreigner like me to work in their health-care system. I'd want to screen that foreigner thoroughly. It only makes sense.

Unfortunately, Canada has determined that a very limited number of physicians is intelligent enough, capable enough to administer their rigorous health-care screening exam (it includes such MENSA-level questions as "Why do you wear glasses?" and "How many teeth have you lost?"). In her infinte wisdom, the Dominion has decreed that, in Liberia, the sole physician designated to ask these general medical questions is a specialized surgeon. Never mind that I'm living on a hospital ship.

This was discovered, naturally, after a phone call from the consular agent informed me that, in Liberia, the sole physician desginated to ask these general medical questions is actually in Accra. Which is in Ghana. Which doesn't even border Liberia.

Small border-related gaffe averted, I called the physician's own cell phone, made an appointment directly with him, booked a taxi and headed into Monrovia.

On the Africa Mercy, we have continued to screen patients after our massive screening day in February. And during our screening, a significant number of patients come with problems that we cannot help—ulcers, uterine fibroids, runny noses, coughs, and the rest. After two days spent negotiating the Liberian health care system, I can't say I blame them.

Dante had no canto for this one.

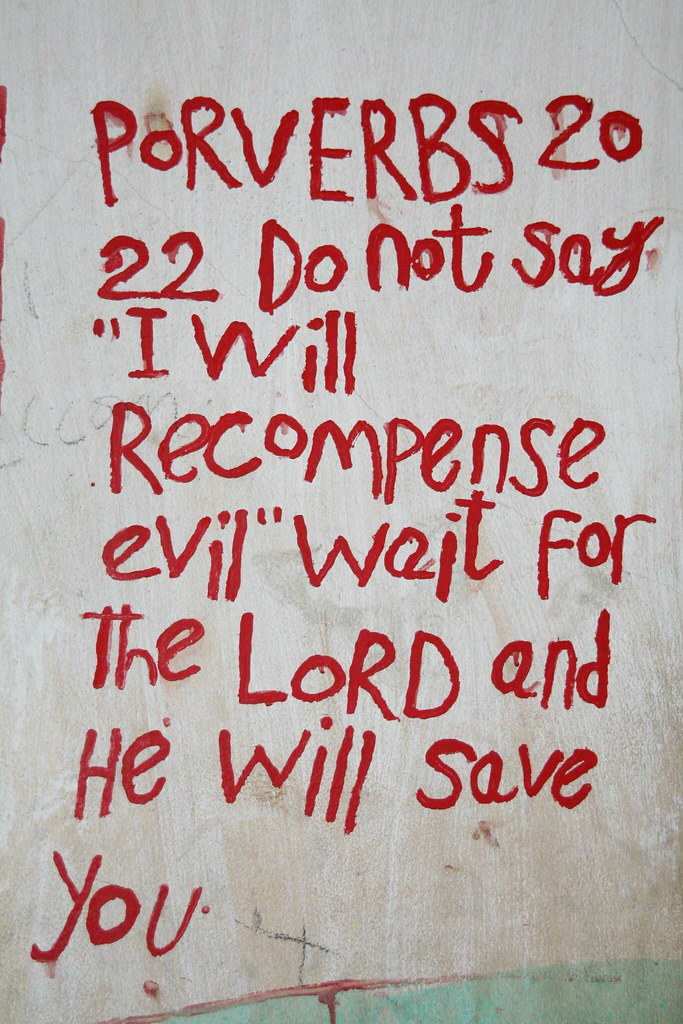

Alfred—the man who, with the patience of St. Sebastian, drove his cab to and from the ship and waited for me while I was in the bowels of the capital city—dropped me off at the clinic. He said he did, at least. If it weren't for a small, hand-painted sign, with a rough blue arrow pointing past an unlit, dank arcade of pirated-DVD sellers, I wouldn't have believed him. But, ducking past the urchins' pleas for me to buy "Black American Slugfest V", and avoiding (not always successfully) the puddles of urine reminiscent of the 190th St. A-train station, I followed the second, hand-painted arrow to the left, past an internet cafe (well sign-posted but eminently nonexistent. Really. It just wasn't there), up the stairs, and into the waiting arms of the actual clinic.

"Hello, I have a two-o'clock appointment with Dr. ————,*" I told the receptionists. They looked at each other, wide-eyed. One motioned for me to sit down, while other said to him, in outright stage-whisper, "I haven't seen him all day!" I suppose they assumed my Liberian English wasn't up to snuff.

Turns out His Eminence was there. He was just having his lunch. So, consigned to joining the flies, the slowly-turning fan, the fecal walls, and the armed security guards, I waited. Thirty minutes later, I was escorted in to meet His Eminence.

His Eminence's first, and at this point only, question for me was whether I had the money to pay for the pleasure of this experience (and the money was not insignificant; it amounts to 18 months' salary for the average Liberian, or in US equivalence, sixty-one thousand dollars). I assured him that I did. With that, I was sent to see his resident.

His Eminence's Resident's job—the poor man—is to sit behind a desk, collect the monies, and fill out prescriptions, written on the backs of scrap paper, for chest x-rays, urinalyses, blood tests, stool samples (patently not required by the Canadian government, but no amount of arguing could convince His Eminence), and then shoo you out, lest you consume any more of his precious air conditioning.

I was sent first to radiology. Above its door flashed a big, bold, red-lit sign. The X-ray was in use, it said. Entry would be undertaken at my own risk.

I waited.

Until it became obvious that either whatever patient was behind that door had been burnt to an unrecognizable spastic puddle, or that the sign was a lie. I wagered. A small, bespectacled man, worthy of L. Frank Baum's imagination, appeared, visibly annoyed that I'd insisted on paying mind to the man behind the curtain. Emboldened, I flashed my hand-written "CXR" prescription to him and was furtively ushered in and told, in no uncertain terms, to undress.

Of course.

There were, unfortunately, no Jell-O-encrusted horses.

I regret having used up all my adjectives on the Kyrgyz medical system.

The X-ray machine was one that would have done Roentgen proud. It was old. Like, last-century old. Like, Mary Shelley old. It looked something like this:

Only in a further state of disrepair.

And I never got to use it. I was saved by a frantic knock and an acknowledgment, by His Eminence's Resident's secretary, that the images produced in that room would not meet the Dominion's standards. I needed to get my lab tests first, and then head to the Catholic Hospital.

It took another half hour to be acknowledged by the lab personnel—a half hour that could have been spent sterilizing their equipment, for example. Ah, but no. Akon's coming to town in two weeks. We must prepare! I was graced, instead, with the dulcet tones of the lab staff singing, "Nobody want to see us together, but it don't matter no! Cause I got you, babe!"

Dante had no idea.

"Your name?" "Your age?" "Where you live?" "Married?" (why this particular question matters for a stool sample still escapes me.) And, wearing the same pair of gloves with which he's wiped his nose, opened the door, handled lab samples, shaken hands with multiple friends, danced to over-produced Liberian-American hip-hop, and rifled through a collection of old medicine bottles on the floor, the lab tech took my blood. With a sterile needle. Because that covers a multitude.

He sent me on my way with an old Tylenol bottle into which I needed to pee, and a folded up piece of paper holding a used lollipop stick.

The consternation on my face was probably obvious because, without prompting, he gently explained, "You make stool. Then take this"—pointing to the lollipop stick—"and take stool from toilet and put it in here"—pointing to the folded piece of paper. Thus instructed, I was shown the way to the toilet.

It was a hole in the ground in the middle of a brackish miasma of flies, odorants, sweat, and mosquitoes, surrounded by a slippery patina of the remnants of old occupants, backlit on once-white tiles. And it belonged to the family whose house abutted the clinic. I'm not kidding. They ignored me as I walked by.

Those same gloves accepted my frankincense and myrrh. And, finally freed of my requirements, I found Alfred and we raced to the Catholic Hospital (motto: Caring is Unrewarding. I am not making that up).

"Sorry. We're closed."

No, really. Closed! A hospital. "It is night shift. No more X-rays."

It was 3:40. Evidently, the night shift starts mid-day. "You can check in the ER. Maybe they can do an X-ray for you."

To the ER I went. It was empty. A lone, short man emerged from a curtain (Baum struck, once again), and I made my plaintive request. "Who told you we could do an X-ray?" he asked. After I answered, he escorted me back to the front desk. And they started fighting with each other, the receptionist and the short man.

"I didn't tell him. He wanted an X-ray!"

"He said you told him"

"I told you I didn't."

And on, until the short man put his arm on my shoulder, in a very unrewardingly caring way, and said, "Let me explain to you clearly" (clearly! Ok. I'm listening). "We don't do X-rays. It's night shift."

Ah! Thank you, sir. God help the man who actually needs one.

Flummoxed, I crumpled in the car on the way back to the ship, past cries of other street urchins. Kohminerah! Kohmineruatah! (This, by the way, means "Cold mineral water." It comes in sandwich bags, hand-tied.) I got my X-ray done on the ship.

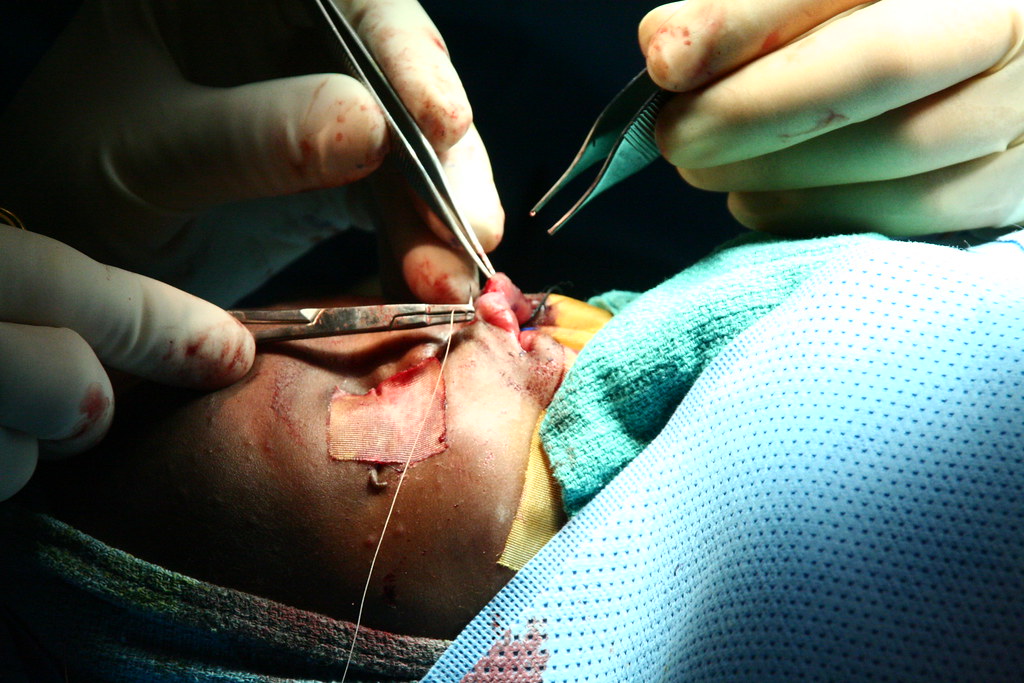

I won't regale you with the details of day 2. With waiting in the same feces-infested room for five hours, beneath the gleeful smiles of the two receptionists, watching bad Nigerian television (you guys missed a riveting episode of Husband My Foot 2, I'm sorry to say), and having His Eminence emerge, at the top of the fifth hour, with widened eyes, a start, and an "Oh! I forgot about you!" Or with the threat—in all seriousness—of bodily harm by the bespectacled X-ray tech if I peeled any more paint off the wall. (I was bored. What can I say?) Or with His Eminence's exceedingly thorough medical exam.

By the time I got back to the ship on Wednesday night, after nine hours of attempting to fulfill the Dominion's requirements for her conditional love and acceptance, I wondered whether Accra wouldn't have been a better choice.

*There are only 40 doctors in Liberia. I'm not about to take a chance.