Liberians are enamored of acronyms, it seems. Every sign, every store name, every window must be bedecked with an abbreviation, to give it—I can only surmise—a sense of import.

Some of these acronyms are eminently obvious: The International Church of Monrovia, for example, is always referred to by its assistant pastor as "The International Church of Monrovia, or ICM for short" (The fact that the offending appendage does nothing to shorten the sentence seems lost. But what do I know?)

Some, on the other hand, are perfectly superfluous. The John T. Fahme Provision Store has JTF, in parentheses, on its awning. Because, naturally, referring to "JTF" must obviously mean a reference for John T. Fahme. Lucky guy. Similarly, should you ever want to refer to God's Executive Praise, you are reminded that you may do so as GEP.

Some are more cumbersome than the names they abbreviate: Why you'd ever be tempted to refer to the War-Affected Women Employment and Empowerment Programme as WAWEEP is beyond me.

And then there are those the simply ironic. Does, for example, the Hope of Glory Conquerer's Chapel recognize the porcine nature of its acronym? Or is the Amputee Rescue Mission trying to be mean? (I think they might be).

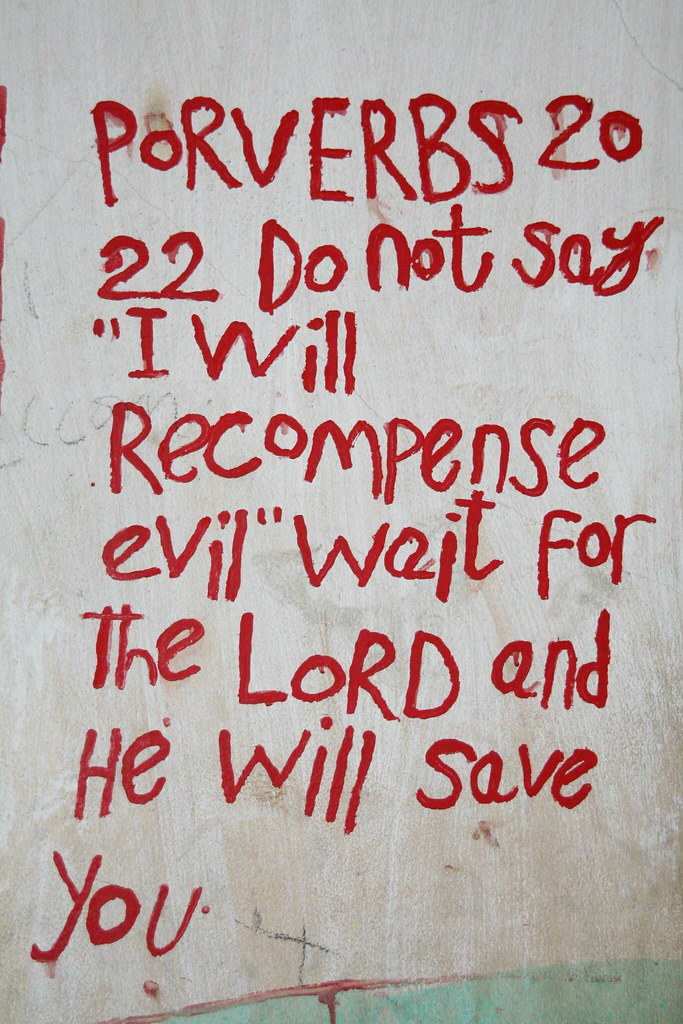

Ah, but then there's my favorite. Because of the disturbing mental image it conjures:

Consider yourself warned.

25 May 2008

God's explosion

Posted by

M

at

5/25/2008 08:23:00 AM

0

comments

![]()

09 May 2008

Can we pull a Moses?

The rains are getting worse.

I ventured out to downtown Water Street with fellow crewmember Megan today. Although overcast, the weather was great. A slight breeze ruffled our hair as we clomped down the gangway in our flip flops and made our way to the main gate. Before I left my cabin, I briefly debated bringing my umbrella. However, a misadventure last weekend had left a small explosion of SPF 50 sunscreen all over it, and so I decided to leave it behind.

It started out as a relatively lucky transportation day. As we walked out of the main gate we started making a lateral chopping motion with our hands (the only proper way to hail a Liberian taxi). After about 5 minutes we were in a run-down yellow cab crammed with 6 other people, on our way into downtown Monrovia. At Broad Street, our driver turned to us and told us we had to switch cabs, to another one going to Sinkor. And so we hopped out and started to search. Buses and taxis passed us by, all too full or too busy going somewhere else. Finally, a guy driving a Cellcom service van stopped and we hopped in, on our way to Sinkor.

We had a quick lunch in Sinkor, and then tried to find another taxi. Again, an unfruitful expedition. Finally, we were picked up by a well-meaning Lebanese contractor, who gave us a ride back to downtown Monrovia.

Hitchhiking has never been my thing. However, in Monrovia, with NGO and UN workers totaling over 10,000, it is often a better bet to get a ride in one of their vehicles than to take your chances with a yellow cab. Yellow cabs here are often crammed 7 people to a car (2 in the front passenger seat and 4 in the back, plus a driver), have cracked windshields, and lack door or window handles. These Nissans and Sunnys are the most prevalent vehicles on the road, and are often plastered with slogans like "City Boy" or "God's Choice." Or worse.

Water Street is known for its fabric shops. The larger, more prosperous shops are Lebanese-owned, with proprietors who travel as far as Dubai where there is a large fabric exchange. Cloth vendors converge from all over the world to hawk their wares, and these fabric shops sell anything from cotton prints and tie-dyes to fine Japanese lace and velvet leopard print. Smaller shops usually line back alleys, and are more wooden shacks with plastic tarp than anything else. Finally individual women and boys carry lappas (one lappa is 2 yards) bundled together in plastic tubs and perched on their heads. These vendors usually sell only African prints, which are always a swirl of color, and on closer examination reveal a repeating motif—chickens, crustaceans, giant tubes of lipstick, or tree stumps.

We were happily browsing on Water Street when the skies opened up. The erstwhile roads and sidewalks quickly became a mess of trash, mud, sewage, and water. With no drains and a fierce tropical storm, we were quickly left knee deep in filth. As we debated how to reach higher ground, the local Liberians, huddled underneath awnings, started to shout things like "Roll up your pants!" and "This is Africa!." That's when Megan turned to me and asked, "Can we pull a Moses?"

Posted by

Peggy

at

5/09/2008 03:03:00 PM

0

comments

![]()

27 March 2008

Caring is unrewarding

As if Kyrgyzstan wasn't bad enough.

Canada, according to its US embassy's website, "prides itself as an open country which welcomes immigrants and visitors." What they don't tell you (it's couched in a benign sounding injunction to "consult the links below") is that their welcome is a very conditional one. Conditional upon the whims of whichever consular agent, for example, is handling your work permit application (the things required of me this year differ significantly—and inexplicably—from those required last year).

One of the conditions placed on this love of Canada is the requirement for a medical exam. Now, I don't fault them. They're intending to hire a filthy foreigner like me to work in their health-care system. I'd want to screen that foreigner thoroughly. It only makes sense.

Unfortunately, Canada has determined that a very limited number of physicians is intelligent enough, capable enough to administer their rigorous health-care screening exam (it includes such MENSA-level questions as "Why do you wear glasses?" and "How many teeth have you lost?"). In her infinte wisdom, the Dominion has decreed that, in Liberia, the sole physician designated to ask these general medical questions is a specialized surgeon. Never mind that I'm living on a hospital ship.

This was discovered, naturally, after a phone call from the consular agent informed me that, in Liberia, the sole physician desginated to ask these general medical questions is actually in Accra. Which is in Ghana. Which doesn't even border Liberia.

Small border-related gaffe averted, I called the physician's own cell phone, made an appointment directly with him, booked a taxi and headed into Monrovia.

On the Africa Mercy, we have continued to screen patients after our massive screening day in February. And during our screening, a significant number of patients come with problems that we cannot help—ulcers, uterine fibroids, runny noses, coughs, and the rest. After two days spent negotiating the Liberian health care system, I can't say I blame them.

Dante had no canto for this one.

Alfred—the man who, with the patience of St. Sebastian, drove his cab to and from the ship and waited for me while I was in the bowels of the capital city—dropped me off at the clinic. He said he did, at least. If it weren't for a small, hand-painted sign, with a rough blue arrow pointing past an unlit, dank arcade of pirated-DVD sellers, I wouldn't have believed him. But, ducking past the urchins' pleas for me to buy "Black American Slugfest V", and avoiding (not always successfully) the puddles of urine reminiscent of the 190th St. A-train station, I followed the second, hand-painted arrow to the left, past an internet cafe (well sign-posted but eminently nonexistent. Really. It just wasn't there), up the stairs, and into the waiting arms of the actual clinic.

"Hello, I have a two-o'clock appointment with Dr. ————,*" I told the receptionists. They looked at each other, wide-eyed. One motioned for me to sit down, while other said to him, in outright stage-whisper, "I haven't seen him all day!" I suppose they assumed my Liberian English wasn't up to snuff.

Turns out His Eminence was there. He was just having his lunch. So, consigned to joining the flies, the slowly-turning fan, the fecal walls, and the armed security guards, I waited. Thirty minutes later, I was escorted in to meet His Eminence.

His Eminence's first, and at this point only, question for me was whether I had the money to pay for the pleasure of this experience (and the money was not insignificant; it amounts to 18 months' salary for the average Liberian, or in US equivalence, sixty-one thousand dollars). I assured him that I did. With that, I was sent to see his resident.

His Eminence's Resident's job—the poor man—is to sit behind a desk, collect the monies, and fill out prescriptions, written on the backs of scrap paper, for chest x-rays, urinalyses, blood tests, stool samples (patently not required by the Canadian government, but no amount of arguing could convince His Eminence), and then shoo you out, lest you consume any more of his precious air conditioning.

I was sent first to radiology. Above its door flashed a big, bold, red-lit sign. The X-ray was in use, it said. Entry would be undertaken at my own risk.

I waited.

Until it became obvious that either whatever patient was behind that door had been burnt to an unrecognizable spastic puddle, or that the sign was a lie. I wagered. A small, bespectacled man, worthy of L. Frank Baum's imagination, appeared, visibly annoyed that I'd insisted on paying mind to the man behind the curtain. Emboldened, I flashed my hand-written "CXR" prescription to him and was furtively ushered in and told, in no uncertain terms, to undress.

Of course.

There were, unfortunately, no Jell-O-encrusted horses.

I regret having used up all my adjectives on the Kyrgyz medical system.

The X-ray machine was one that would have done Roentgen proud. It was old. Like, last-century old. Like, Mary Shelley old. It looked something like this:

Only in a further state of disrepair.

And I never got to use it. I was saved by a frantic knock and an acknowledgment, by His Eminence's Resident's secretary, that the images produced in that room would not meet the Dominion's standards. I needed to get my lab tests first, and then head to the Catholic Hospital.

It took another half hour to be acknowledged by the lab personnel—a half hour that could have been spent sterilizing their equipment, for example. Ah, but no. Akon's coming to town in two weeks. We must prepare! I was graced, instead, with the dulcet tones of the lab staff singing, "Nobody want to see us together, but it don't matter no! Cause I got you, babe!"

Dante had no idea.

"Your name?" "Your age?" "Where you live?" "Married?" (why this particular question matters for a stool sample still escapes me.) And, wearing the same pair of gloves with which he's wiped his nose, opened the door, handled lab samples, shaken hands with multiple friends, danced to over-produced Liberian-American hip-hop, and rifled through a collection of old medicine bottles on the floor, the lab tech took my blood. With a sterile needle. Because that covers a multitude.

He sent me on my way with an old Tylenol bottle into which I needed to pee, and a folded up piece of paper holding a used lollipop stick.

The consternation on my face was probably obvious because, without prompting, he gently explained, "You make stool. Then take this"—pointing to the lollipop stick—"and take stool from toilet and put it in here"—pointing to the folded piece of paper. Thus instructed, I was shown the way to the toilet.

It was a hole in the ground in the middle of a brackish miasma of flies, odorants, sweat, and mosquitoes, surrounded by a slippery patina of the remnants of old occupants, backlit on once-white tiles. And it belonged to the family whose house abutted the clinic. I'm not kidding. They ignored me as I walked by.

Those same gloves accepted my frankincense and myrrh. And, finally freed of my requirements, I found Alfred and we raced to the Catholic Hospital (motto: Caring is Unrewarding. I am not making that up).

"Sorry. We're closed."

No, really. Closed! A hospital. "It is night shift. No more X-rays."

It was 3:40. Evidently, the night shift starts mid-day. "You can check in the ER. Maybe they can do an X-ray for you."

To the ER I went. It was empty. A lone, short man emerged from a curtain (Baum struck, once again), and I made my plaintive request. "Who told you we could do an X-ray?" he asked. After I answered, he escorted me back to the front desk. And they started fighting with each other, the receptionist and the short man.

"I didn't tell him. He wanted an X-ray!"

"He said you told him"

"I told you I didn't."

And on, until the short man put his arm on my shoulder, in a very unrewardingly caring way, and said, "Let me explain to you clearly" (clearly! Ok. I'm listening). "We don't do X-rays. It's night shift."

Ah! Thank you, sir. God help the man who actually needs one.

Flummoxed, I crumpled in the car on the way back to the ship, past cries of other street urchins. Kohminerah! Kohmineruatah! (This, by the way, means "Cold mineral water." It comes in sandwich bags, hand-tied.) I got my X-ray done on the ship.

I won't regale you with the details of day 2. With waiting in the same feces-infested room for five hours, beneath the gleeful smiles of the two receptionists, watching bad Nigerian television (you guys missed a riveting episode of Husband My Foot 2, I'm sorry to say), and having His Eminence emerge, at the top of the fifth hour, with widened eyes, a start, and an "Oh! I forgot about you!" Or with the threat—in all seriousness—of bodily harm by the bespectacled X-ray tech if I peeled any more paint off the wall. (I was bored. What can I say?) Or with His Eminence's exceedingly thorough medical exam.

By the time I got back to the ship on Wednesday night, after nine hours of attempting to fulfill the Dominion's requirements for her conditional love and acceptance, I wondered whether Accra wouldn't have been a better choice.

*There are only 40 doctors in Liberia. I'm not about to take a chance.

Posted by

M

at

3/27/2008 04:36:00 PM

5

comments

![]()

01 March 2008

Synecdoche

As far as I can piece together from the Nigerian UN soldiers patrolling the hotel, a Liberian security guard (mostly guarding his spot in the shade), Google, and our friend Megan, the hotel was built by a Libyan company in the 1970s, at the peak of Monrovia's stint as a top-choice travel destination, and has passed through multiple owners, including the Intercontinental group of hotels. At its prime in the 1980s, a night at the hotel would set you back between $150 and $200 (that's around $400 in today's currency). And then the war started.

During the war, the hotel shouldered a number of disparate roles: as temporary headquarters of the President, the government's forces, the rebel's forces, and finally—until May of last year—as a refugee camp for up to 2500 of the internally displaced.

Since May, it's become a concrete shell, home only to a few kids whose school meets on the second floor, a church, and a requisite UN presence. And the daily influx, it seems, of amateur photographers from any of the NGOs in this country, equipped with cameras worth more than they should be, and a keen awareness of the unjust dichotomy they create.

From the lens of one of those cameras, a few pictures:

Posted by

M

at

3/01/2008 04:11:00 PM

0

comments

![]()

24 February 2008

Potpourri for $200

President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf's visit to the Africa Mercy:

Monrovia from a car window:

Posted by

M

at

2/24/2008 10:43:00 AM

1 comments

![]()

16 February 2008

Appearances can be deceiving

Perhaps we have been travelling too long. We finally made it into downtown Monrovia today. Sometimes seeing too many things makes you stop paying attention to the details. The city looked poor, but not war torn. Yes, there was trash lying in the gutters, people selling things out of baskets, and potholes determined to rattle your teeth. But at least the roads are paved. There was also a store selling Dell computers, another one called "Radio Shack," and the "Heineken store" selling Frosted Flakes, Lipton Peach Iced tea, and Splenda. Really, if you ignored the occasional UN vehicle and the abundance of barbed wire, how was this different from another third world country such as India?

Perhaps we have been travelling too long. We finally made it into downtown Monrovia today. Sometimes seeing too many things makes you stop paying attention to the details. The city looked poor, but not war torn. Yes, there was trash lying in the gutters, people selling things out of baskets, and potholes determined to rattle your teeth. But at least the roads are paved. There was also a store selling Dell computers, another one called "Radio Shack," and the "Heineken store" selling Frosted Flakes, Lipton Peach Iced tea, and Splenda. Really, if you ignored the occasional UN vehicle and the abundance of barbed wire, how was this different from another third world country such as India?

Posted by

Peggy

at

2/16/2008 10:20:00 AM

0

comments

![]()

10 February 2008

A foray into Monrovia

Posted by

M

at

2/10/2008 11:35:00 AM

1 comments

![]()